...and why it's not that important really.

As a filmmaker and DOP, I am often asked whether expensive and large film- and video cameras are actually still needed today, because after all, every smartphone can shoot 4K. Doesn't it?

In order to answer this question, first it must be clarified what 4K really means. The term reflects the horizontal resolution of the image, which is 3,840 pixels, or in other words, about 4000 pixels (k=kilo=1000). Smaller resolutions would be 2k with 2,048 pixels and HD with 1,920 pixels. So 4K only says something about how big the picture is, but nothing about how good it is. For the quality of the image, loads of other factors are important, frankly, the size of the image is actually rather unimportant.

In order to understand what is responsible for how good or bad an image is, you need to know how the image is captured in the first place.

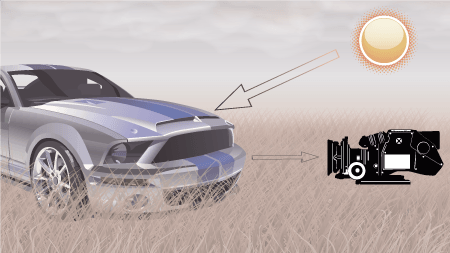

Whether it's a large film camera, a smaller camcorder or a smartphone, the optical process is the same:

Light hits a subject, i.e. an object, a person or both, is reflected from there and falls into the lens of the camera. Here it passes through various optical elements until it hits a photosensitive surface inside the camera and exposes it. With analogue film cameras, this is the film strip, with modern digital film cameras it's the chip and with older video cameras it's a beam splitter followed by three chips (one for each basic colour).

From the moment the light hits the lens, the differences between cameras become noticeable. Even if some mobile phone manufacturers use terms such as Zeiss optics or the like, only tiny and very simple optics are used here. There's a reason, large film lenses easily set you back around $50k to $100k. But even affordable lenses within the range of only a few hundred dollar, as they are used e.g. for mirror reflex cameras, play in a completely different league than the optics in your telephone when it comes to image quality.

Next, the size of the chip plays a decisive role, because the bigger it is, the more photons it can collect. It is important to note that the number of pixels remains the same no matter how big the chip is (at 4k it is 8,294,400 pixels/pixel). To make them fit, the pixels of a small chip, quite simply, are smaller as well. Due to the design alone, the chip in a smartphone is of course considerably smaller than the one in a full-grown film camera. But when the pixels are smaller, less image information can be collected and, in addition to many other effects, the so-called dynamic range shrinks. Ok, npw what is that?

Imagine a completely dark room. Here we have no dynamics whatsoever, the light is simply off. Lighting a single candle gives us 1 f-stop: on and off, black and white. The candle represents the brightest light available on earth. The dynamic range shows the number of gradations between the brightest and darkest signal that the camera can capture. One f-stop more is synonymous with a doubling of the dynamic. The human eye can pick up around 22 f-stops, a professional film camera between 14 and 16 f-stops and a modern smartphone between 8 and 9, which is considerably less. And how does that affect you?

Let me explain this with an example.

Imagine (or play with it live): you are in a living-room, the light is off and the outside it is bright. You look in the direction of a window under which there is a radiator. What do you see? You can see exactly what is in front of the window, e.g. trees, other houses, the sky, clouds etc., but you can also see that you should dust behind the heater. So the human eye is able to pick up very bright and very dark areas of an image simultanously. But what about your smartphone? Things look a bit different there. You have to adjust the exposure depending on what you want to see correctly. Expose bright enough to see the dark area of your heater, the window "burns out" and that's left is white. If you expose the window the other way round, the area behind the heater gets too dark and you only see black. This is one of the reasons why so many spotlights are used on film sets, the differencee between very bright and very dark is reduced, but film cameras already record considerably more dynamics than a smartphone or even a SLR camera.

Another very important point is the color processing of the camera. How many colors can it record? While smartphones and SLR cameras record at 8bit, film cameras usually record at 10bit. It's not sooo much more, you might think. In truth, 8bit means 16.9 million colors, while at 10bit we can fall back on 1.07 billion colors. But, no matter if 8 or 10 bit, how the colors are processed internally, has a huge influence on how natural the image looks afterwards.

Even though it's always good to shoot with the highest possible resolution, professional filmmakers pay attention to entirely different values when choosing the right camera. For example, the Arri Alexa Classic is still one of the most popular cameras and it is used in many large Hollywood and advertising productions, even though no 4K is available. But the color architecture is of the chain, producing beautiful, naturally looking skintones and colors that are hardly matched to this day.

At the very end of the path from sun to object and into the camera, of course there is the data format in which the camera writes the footage. SLR cameras, system cameras and smartphones (without additional software) always store videos in a highly compressed data format. In most cases the h.264 codec is used in an mp4 container or similar. The data rate is usually in the range of a few thousand kb/sec. This data format is very well suited for storing video material in as small a form as possible, which is absolutely sensible in the cases mentioned, because on the one hand there is only limited storage space available and on the other hand films shot with a smartphone are more often than not, directly uploaded to YouTube, Instagram, Facebook or the likes via mobile data network. With film cameras, on the other hand, these factors do not play a role at all and it's above all all the quality of the material that matters. Depending on the application, compression methods such as the DNxHD or XDCAM codec are used, but these do not reduce the footage as much as is the case with "consumer devices". In large film productions, quality is usually the only issue, which is why RAW is the most common format for filming. This format looks somewhat different from manufacturer to manufacturer, but what they all have in common is that the material is available in almost uncompressed single images with the maximum amount of image information. This data format gives everyone later involved in post-production the greatest possible freedom and possibilities in colour design and post-processing of the images. We're talking about something like 16mb per frame/single image, which clearly doesn't fit on a smartphone. With an average of 64 gb storage space, you wouldn't be able to shoot very much. Although the quality of modern compression methods is surprisingly good, such a reduction doesn't come without a massive loss of quality. In comparison, it becomes clear:

SLR camera/smartphone: h.264 codec, 3266 kb/s = 3.19 mb/s = 191.4 mb/min

Broadcast camera: XDCAM HD: 30.96 mb/sec = 1,857.6 mb/min = 1.8 gb/min

Broadcast camera: DNxHD 145: 89.42 mb/sec = 5,362.2 mb/min = 5.2gb/min

Film camera: RAW = 16 mb/frame x 24 = 384 mb/s = 23.040 mb/min = 22,5 gb/min

CONCLUSION: 4K is beautiful, but it is just one of many factors to determine the quality of a film.

We would be happy to advise you personally, simply call us at +49 (0) 42 98 / 18 98 895, send us an e-mail at